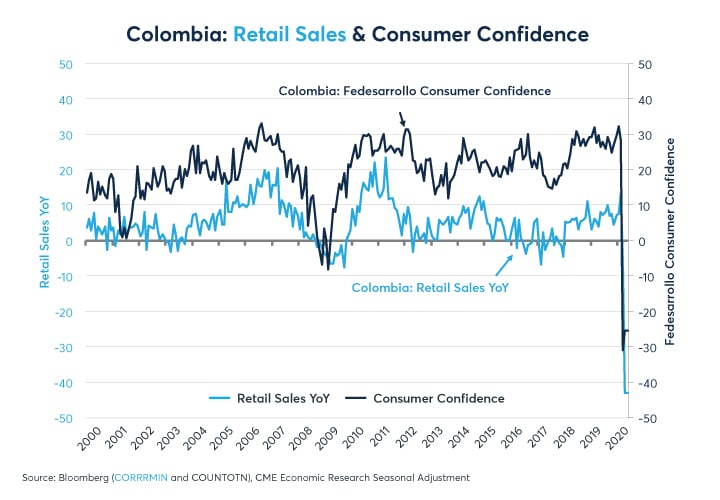

Colombia’s economy has been hit hard by both domestic and international coronavirus lockdowns. Retail sales fell by 40% year-on-year in April, and consumer confidence remained low in May, suggesting another month of bleak retail sales (Figure 1). Meanwhile, unemployment surged to a seasonally adjusted record high of 23.6% in April (Figure 2). Colombia’s central bank has been slashing interest rates and has indicated that it may soon reduce rates to negative levels in real terms. With core inflation at 2% year-over-year recently, that implies the potential for another 100 basis points or more of rate cuts from the current 3.25%. Banco de la Republica Colombia’s decision will come on June 30. In the meantime, the Fedesarrollo (Foundation for Higher Learning and Development) consumer confidence data for June will be released on June 24 offering an insight into consumer sentiment.

Figure 1: Colombia suffered an unprecedented fall in retail sales in April

Figure 2: Past rate-cut cycles had translated into lower unemployment

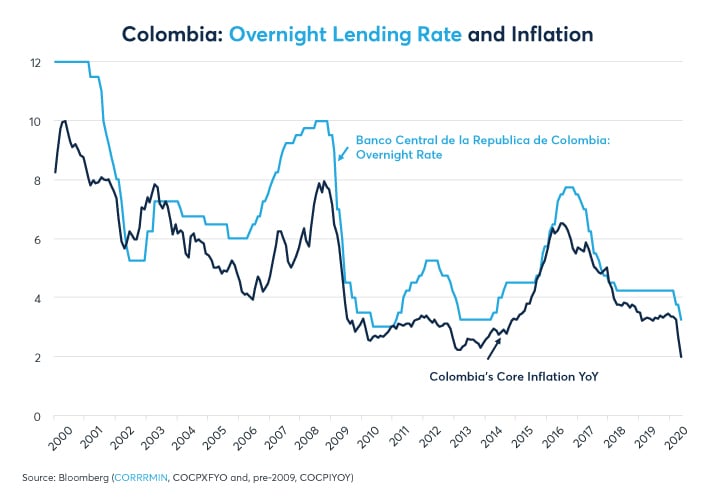

That inflation has fallen to a record low (since the current series began in 2000) is welcome news for Colombia in that it gives the central bank plenty of room to ease policy further. Over the past 20 years, the central bank has generally kept its overnight lending rate about 1-2% above the rate of core inflation. Indeed, a period of low rates from 2002 to 2006 was blamed for a ramp up in inflation from 4% to 8% in 2007 and 2008. Another period of low rates from 2010 to 2015 may have contributed to a rise in inflation from 2.5% to 6.5% in 2016 and 2017 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Colombia’s central bank usually likes to keep its overnight rate above inflation

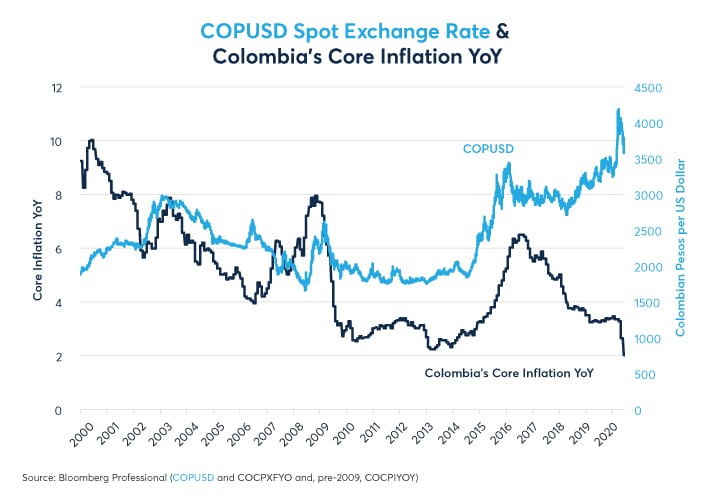

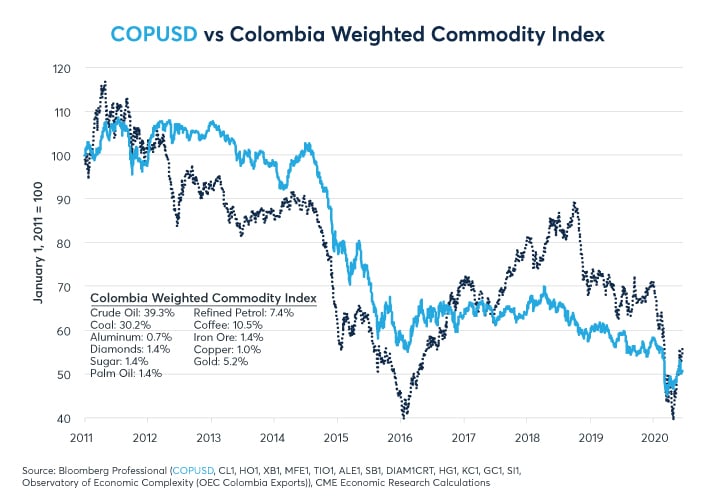

Previous increases in inflation rates coincided with deprecations in the Colombian peso (COP) versus the US dollar (USD). A fall in the peso in 2002 was followed about six months later by a rise in inflation from 6% to 8%. A sharp fall in the peso in 2014-16 preceded a rise in inflation in 2015-17 by about 12 months (Figure 4). This could become a concern for Colombia’s central bank in the future, possibly leading it to reverse course and raise rates. That said, low commodity prices and a major, if not unprecedented, slack in the labor market may keep a lid on inflation despite recent weakness in the COPUSD exchange rate.

Figure 4: Past episodes of currency weakness have often translated into temporary upticks in inflation

Moreover, unlike in the 2000s, when Colombians were still haunted by memories of high inflation in the 1980s and 1990s, inflation expectations now appear to be well anchored following the decline in inflation between 2000 and 2010 and mostly low inflation during the 2010s. Nevertheless, Colombia’s central bank will likely keep a close eye on the exchange rate as a possible harbinger of higher inflation should the currency weakness persist.

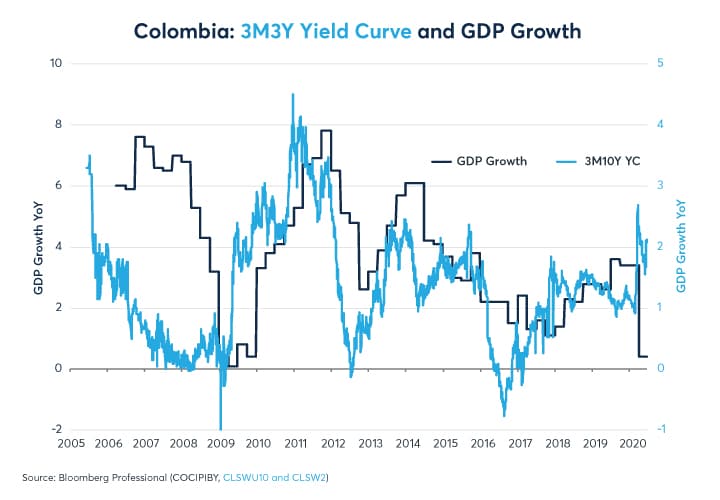

Despite Colombia having had a rough couple of months, recent rate cuts and expectations of further policy easing have dramatically steepened its yield curve. Typically, steep yield curves are a sign that economic growth is about to improve and, indeed, over the past decade and a half, Colombia’s yield curve has shown itself to be a decent indicator of future economic growth. A period of yield curve steepness in 2009 and 2010 was followed by growth rates as strong as 8% year-on-year in 2011 and 2012. A yield curve steepening in 2012 and 2013 was followed by a rise in growth from 2.7% to 6.1% in 2013 and 2014. A more modest curve steepening in 2017 and 2018 was followed by a rise in growth from 1.5% to 3.5% about one year later (Figure 5). Periods of yield curve flatness were often followed by much slower growth.

Figure 5: Colombia’s yield curve is the steepest since 2014 and may be a harbinger of growth

As such, fixed-income markets seem to be sending positive signals. In any case, should Colombia’s central bank opt for further rate cuts, that could steepen the curve further and, generally, the steeper the curve, the stronger the subsequent rebound in economic growth.

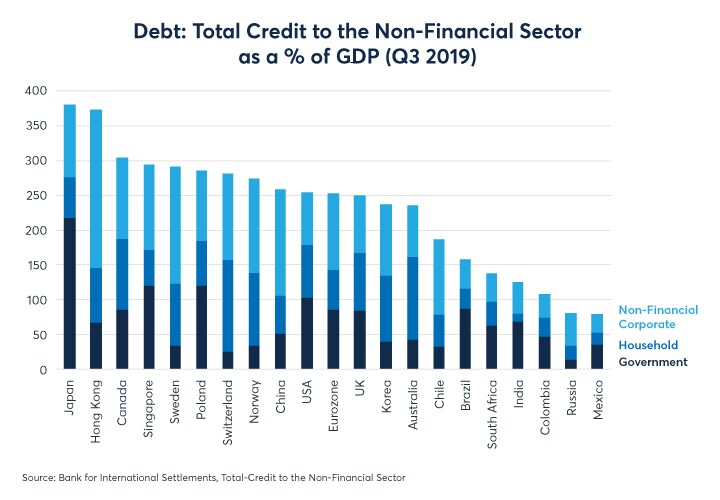

Low inflation and low interest rates aren’t the only strength in Colombia’s economy. The country also has some of the world’s lowest debt levels. In fact, compared to the major economies, only Mexico and Russia have lower levels of debt (Figures 6 and 7). Nations with low debt levels can often stimulate their economies more readily through monetary and fiscal policy. In low-debt nations, additional borrowing by either the public or private sector can quite quickly translate into increased investment or spending, adding to GDP. By contrast, in high-debt nations like China, Japan, US and their peers in Western Europe, additional borrowing mainly serves to finance existing debt and has less marginal impact on boosting growth. This may explain why yield curves in Japan, US and Western Europe remain flat despite rapidly rising budget deficits and zero, or even negative, interest rate policies.

Figure 6: Colombia has among the world’s lowest levels of debt

Figure 7: Colombia’s total public and private sector debt has remained stable since 2015.

Colombia’s low levels of debt may partly explain why Colombia’s currency has remained relatively stable despite the sharp fall in the value of its commodity exports (Figure 8). In the past, falling commodity prices produced much bigger moves in the currency. This time, however, investors appear to have become more discerning and currencies of highly indebted emerging markets, like Brazil, have had a tougher time than less indebted ones like Colombia and Mexico (Figure 9).

Figure 8: Colombia is known for coffee but oil and coal dominate its exports

Figure 9: Lower-debt MXN and COP have outperformed higher-debt BRL

Bottom Line

- Colombia’s steep yield curve suggests a strong rebound in growth

- Colombia’s central bank’s ability to keep rates low depends on inflation

- Low levels of debt could help Colombia engineer an economic rebound

- Low debt could explain COP resilience in the face of weaker export prices

To learn more about futures and options, go to Benzinga’s futures and options education resource.

© 2024 Benzinga.com. Benzinga does not provide investment advice. All rights reserved.

Comments

Trade confidently with insights and alerts from analyst ratings, free reports and breaking news that affects the stocks you care about.